Start your Learning Here

- Module 1 – Fiji’s Approach to Youth Development

- Relevant SDGs, FNDP and SDG Review

- Module 2 – A Local Insight

- Hear from Teachers, Youths and Academics

- Module 3 – The Barriers and Challenges Influencing Quality Education in Fiji

- Challenges Breakdown

And to get you thinking – here is Lulu’s vision from 2016

Module 1: Fiji's Approach to Youth Development

The Fiji National Development Plan was launched by the Fiji Government in November 2017 with the vision of ‘Transforming Fiji’, and provided a framework for ‘all Fijians to realise our full potential as a nation’.

UNESCO believes that education is a human right for all throughout life. They highlight the importance of education and believe it plays an integral part in eradicating poverty, establishing peace and driving sustainable development. Education is a fundamental right and provides the foundation for members of society to be rational and recognise other rights. It is through education, that a nation has the ability to achieve growth, development and prosperity.

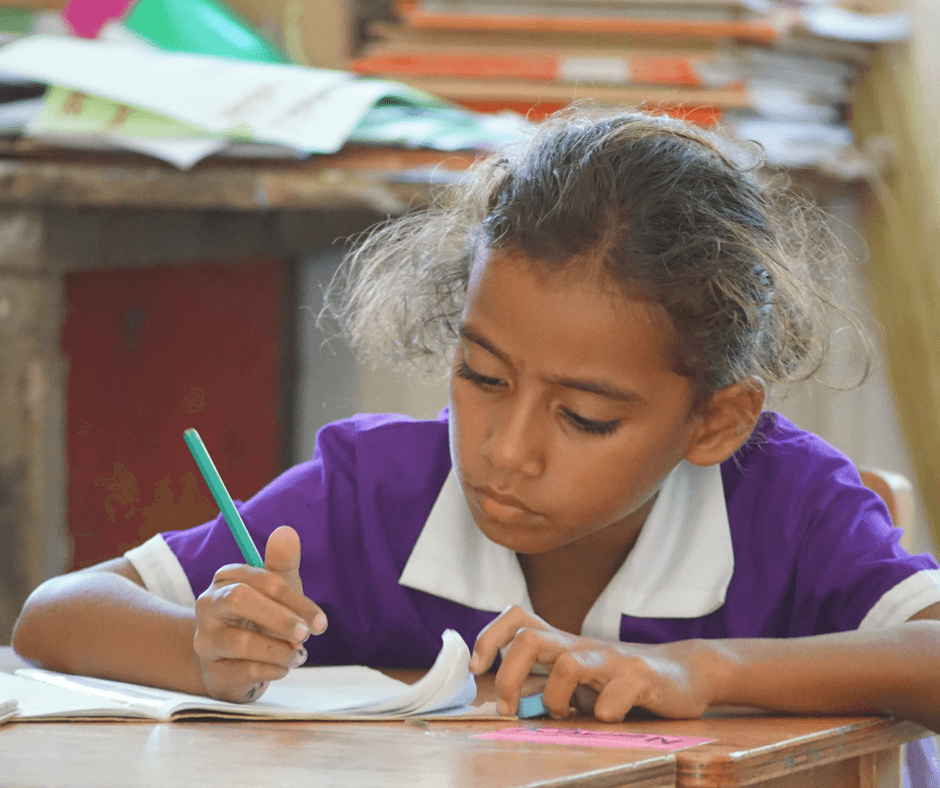

The Fiji Ministry of Education, Heritage and Arts is the main facilitator within the achievement of the National Development Plan Education priorities. The FNDP states that quality education for all is essential to create a more skilled and adaptable workforce and create a knowledge-based society. The Constitution guarantees the right of every child to early-childhood, primary, secondary and further education.

Fiji provides education through grade school in most communities, including rural and isolated communities, and through high school in most urban centres. Beginning in 2013, school fees are now paid by the government, thus removing the economic strain felt by many families in having to pay school fees for multiple children, which in the past caused many children to miss entire years of school. The FNDP states how universal access to primary education has been achieved, and net secondary school enrolment is over 80 percent. The free-education initiative also includes free bus fares and free textbooks, which has also positively contributed to the significant increase in enrolment numbers. Nevertheless, parents and caregivers still have to pay for uniforms and school supplies, including book fees, which remains onerous for many families.

The UN SDG4 is to ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all

The United Nations Development Programme note the SDG’s aim is to ensure that all girls and boys complete free primary and secondary schooling by 2030. Introducing inclusive and quality education for all demonstrates the belief that education is a proven vehicle for sustainable development and essential to achieving many other SDGs.

Despite years of steady growth in enrolment rates, 262 million children and adolescents remain out of school worldwide.

‘When people are able to get quality education they can break from the cycle of poverty.

Global Statistics

– 57 million primary-aged children remain out of school

– In developing countries, one in four girls is not in school.

– 103 million youth worldwide lack basic literacy skills, and more than 60 percent of them are women.

– 6 out of 10 children and adolescents are not achieving a minimum level of proficiency in reading and math.

Module 2: The local Insight

This module is your chance to learn from those heavily involved in working with youths or are youths themselves. They discuss the challenges of their industry and the challenges of growing up in Fiji. As you listen to each of these interviews consider how their circumstances or position may have influenced their perspective.

Module 3: The Barriers and Challenges Influencing Quality Education in Fiji

The Fiji Islands are a republic of over 330 islands, covering more than 18,000 square kilometres. The nature of this geography poses significant challenges for the delivery of quality educational services to a population that is dispersed over such a large maritime region.

The Introduction of the Fiji National Curriculum Framework (NCF) by the Ministry of Education (2007) and its more recent second edition (MEHA 2013) signified a progressive reform on how Fijian Education was to be considered. The need for change came about as the previous curriculum was seen to be too teacher-centred and exam-orientated. The new framework envisaged a holistic approach, child-centred learning and the teacher being seen as more of a facilitator.

However, these progressive reforms were short-lived, as in 2015 the MEHA re-introduced standardised exams and abolished the student-centred assessment process. These ever-changing reforms are having a negative effect on the system as a whole and restricting Fijian education from its potential.

Although the NCF’s holistic approach and liberal vision still remains the primary guiding framework, the recent conservative and performative reforms have meant the implementation and structure are not aligned with the overall objective and mission.

There is a lot of disparity between urban and rural schools across the country. Many of the biggest challenges exist within the rural and remote locations such as: lack of resources, basic or outdated facilities, poor quality textbooks, limited access to technology and lack of support and assistance due to the locality.

Although most schools are operated by non-government organisations, they all follow the ministry’s policies and curricula, while the school management boards are the bodies responsible for the maintenance and development of school facilities (Lingam, 2009). The multiplicity of ownership of schools contributes to major differences in the standards of school facilities and resources. Where these may be lacking there is a resultant burden on the families of lower socio-economic status. Those living in rural areas and are solely reliant on subsistence farming may require the support of the young children to work the land. Those living in improvised settlements in the city

A lot of the Teacher-related challenges filter down from the school barriers, with a lack of resources being evident both from a human resource perspective and one of material-resources. From our experience of working in many schools across Fiji, the student-teacher ratios are a consistent issue. Many classes are composite meaning the teacher is stretched delivering 2 separate lessons. This common structure provides heavier workloads, increased paperwork and, as well as that, the teachers are also responsible for the extra-curricular activities.

Studies found that teachers felt increased stress through increased formal accountability, closer monitoring by the Ministry of Education, limited promotion opportunities and time constraints over delivering an overloaded curriculum into the school year. (Crossley et al, 2017). The same study also found that the majority of teachers believed that ‘they are not well respected in society’ and this decline in societal respect results in a ‘lack of appreciation for them as professionals’.

There’s no surprise that all the issues mentioned above have an effect on the student experience. Since 2009 we have supported primary schools across 9 of the 14 provinces and a common theme is the disparity across the students’ learning needs and the difference in ability. Within an overcrowded classroom consisting of composite year groups, the possibility of a student’s individual needs being met is minimal. This causes a negative ripple effect as certain students become disengaged, resulting in a poor attitude towards learning and behaviour. The student then begins to fall further behind but with no contingency or extra support available, they begin to become frustrated with the system, leading to poor attendance and eventually dropping out.